European leaders (plus Canada) held a second emergency summit yesterday (Wednesday) as the continent grapples with a rapidly shifting security outlook. Why?

The catalyst is not so much any change in Russia’s ongoing invasion of a European country (Ukraine) — in fact, any Russian momentum has slowed this month. Rather, it’s a change in the way the US approaches the world, driven by a change in US president:

- From a historical perspective, Trump is now signalling the winding-back of a 75-year old defensive alliance, whether because the US can’t (gotta focus on China) or won’t (divergence in values) prioritise European security much longer, and

- From an immediate perspective, Trump is now calling Ukraine’s Zelensky a dictator and blaming him for Putin’s decision to send tanks over the border, missiles into Ukrainian cities, and nuclear threats out at the broader West.

And even if that reflects Trump’s campaign and beyond, this US 180° has caused whiplash.

Stay on top of your world from inside your inbox.

Subscribe for free today and receive way much more insights.

Trusted by 134,000+ subscribers

No spam. No noise. Unsubscribe any time.

So where does it leave Europe?

From an economic perspective, Europe is a (beleaguered) giant: ten times the GDP of Russia, which in turn has a smaller economy than (say) Italy, Canada, and even Texas.

And that’s played out in Europe’s support for Ukraine, totalling $137.9B since Russia’s invasion, versus $119.1B from the US. It’s a similar story if you zoom into security assistance, with Europe contributing $65B and the US $67B (spent mostly within the US).

But given the stakes for Europe (not protected by a “big, beautiful ocean”), some argue its biggest economies can and should do more. Sure, Europe’s main engine (Germany) is also its top contributor to Ukraine, but it’s still totalling 0.5% of GDP, and that figure gets even smaller as you swing through Paris, Rome, and Madrid. It’s only nearer Russia’s border (Northern Europe, the Baltics, and Poland) where support for Ukraine clears 1%.

Then from a military deployment perspective, the picture just gets murkier — the UK and France have flagged deploying peacekeeping troops in Ukraine to deter more Russian aggression. But credible estimates suggest you’d need 100,000 troops to deter another Russian invasion, and even before you get into the how, Russia has already rejected the idea as “unacceptable”, and nobody else is raising their hand.

Why? It’s partly because deploying troops to Ukraine weakens Europe’s deterrence elsewhere, just as the US is flagging its own draw-down. And that also leaves Europe in a bind, with its troops in Europe backed by a NATO pledge, while its troops in Ukraine are not. That’s a gap that any competent adversary could exploit to weaken an alliance.

But both these economic and military questions are really downstream of something bigger: political will to continue backing Ukraine. Sure, those bordering Russia — or with a history of Russian occupation — view Moscow’s invasion of Ukraine as existential; Putin could use his same justifications (history, Russian-speakers, security) to hit them next.

Others, like Hungary’s Viktor Orbán (a perennial blocker of EU aid), argue “the war in Ukraine could become easily an Afghanistan for the EU”. And even among those with less cushy Moscow ties, Russia is still sometimes seen as a more distant threat, particularly amid the more immediate political and economic crises back home.

So what’s next?

Europe’s second emergency summit didn’t deliver any obvious answers overnight, but it did nudge a breakthrough: Mike Waltz (Trump’s national security advisor) just announced France’s Macron and the UK’s Starmer are invited to talks at the White House next week.

INTRIGUE’S TAKE

Ultimately, history might conclude that firmer and quicker support from Europe (and Biden) could’ve enabled Ukraine to fend off Russia’s invasion completely, rather than enabling Putin to hang on long enough for a new US president to make concessions.

But zooming out further, there’s another possible ripple effect from what’s now happening between the US and Europe — an increased risk of nuclear proliferation.

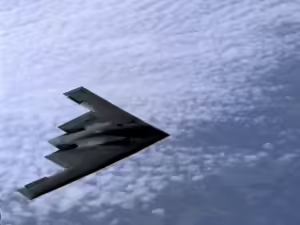

Traditionally, there’s been no need or scope for US allies to pursue nuclear weapons, because allies could just rely on US security pledges instead. But as those US pledges decline in value (perceived or actual), capitals will rethink their approach to nukes. You’d be surprised how quickly taboos can evaporate when folks feel a threat is existential.

Also worth noting:

- The EU just approved its 16th round of sanctions against Russia.