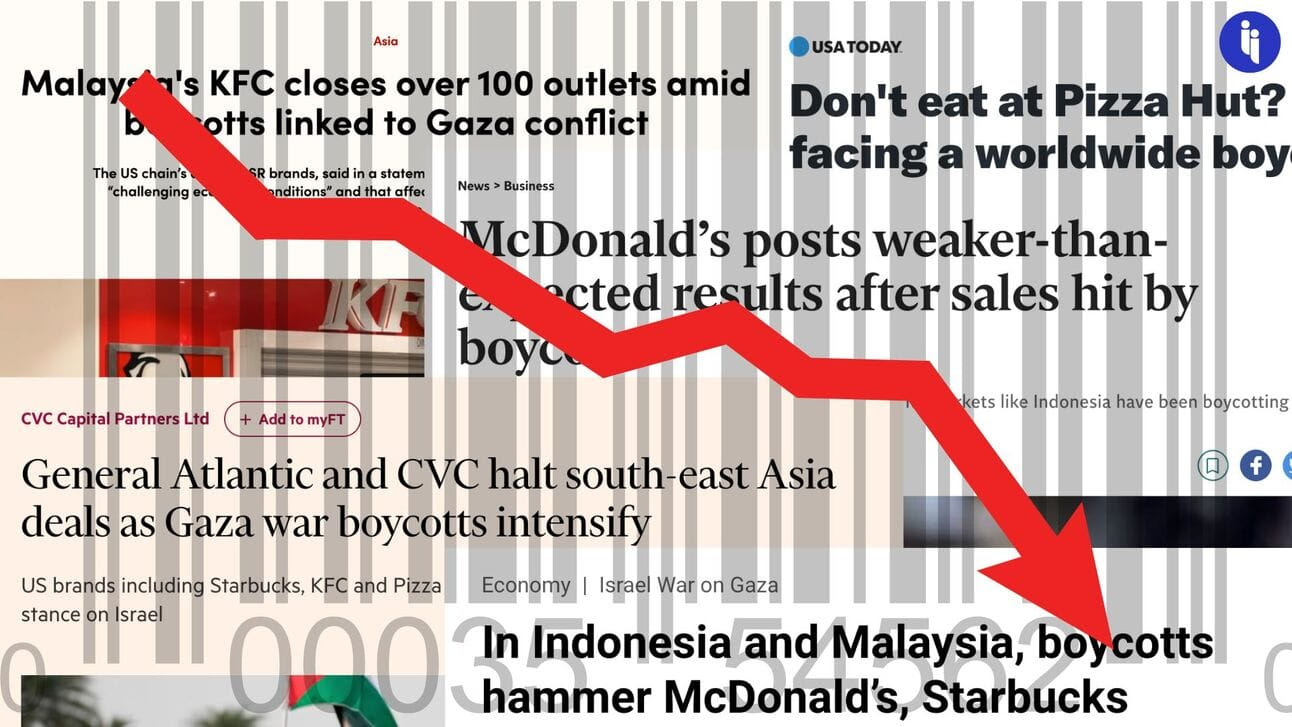

The Malaysian operator of fast food giant Kentucky Fried Chicken (KFC) announced on Monday it was temporarily closing outlets across the country, citing “challenging economic conditions”. Local media then said the quiet bit out loud: 100 or so KFC outlets are closing in Malaysia due to an ongoing boycott.

This latest boycott is one of several around the world targeting businesses seen to be supporting – or in any way linked to – Israel’s actions in Gaza.

In KFC’s case, local activists called on folks to stop buying from the Colonel because the parent company Yum! Brands is an investor in Israeli startups.

Stay on top of your world from inside your inbox.

Subscribe for free today and receive way much more insights.

Trusted by 134,000+ subscribers

No spam. No noise. Unsubscribe any time.

Rival chain McDonalds has also faced boycotts around the world after outlets in Israel provided free food to Israeli soldiers in the wake of the Hamas attacks.

And Starbucks got embroiled in boycotts when it sued a union of US employees for copyright breach, after the union retweeted an image of a bulldozer breaking through the Israel-Gaza barrier. The union’s since-deleted post, sent shortly after the Hamas attacks on Israel, added the comment “Solidarity with Palestine!”

Others have pointed to Howard Schultz, former Starbucks CEO and major shareholder, and his recent investment in an Israeli cybersecurity startup.

While the boycott details vary, the results are starting to look similar:

- Starbucks has cut its yearly sales forecasts and let hundreds of staff go due in part to slowing traffic in its Middle East locations

- McDonald’s has missed a key sales target and identified Malaysia, Indonesia, the Middle East, and France as markets being hit by boycotts, and

- The Middle East’s operator for KFC and Pizza Hut has cut 100 or so jobs amid “recent regional geopolitical tensions”, while the Malaysian KFC operator has (again) now shelved its planned IPO.

These brands, which operate mostly via local franchisees and licensees, have sought to mend the damage in various ways: McDonald’s HQ is reclaiming control of the entire Israeli franchise after three decades, while McDonald’s Malaysia (“a 100% Muslim-owned entity”) sued local activists last year.

Likewise, the local Starbucks operator in Malaysia has emphasised it’s actually Malaysian-owned (“we don’t even have one foreigner working in head office or stores”), while Starbucks has donated to World Central Kitchen.

But the above examples suggest this phenomenon is particularly (though not exclusively) acute in Muslim-majority regions like Southeast Asia, where damage to US corporate brands is dove-tailing with broader damage to the US national brand – a trend even highlighted by the regional head of Domino’s!

This broader US branding issue in turn risks filtering through to US-China competition across the Indo-Pacific, now a pivotal region for this century.

INTRIGUE’S TAKE

This is all another example of how globalisation’s strengths now risk becoming its vulnerabilities:

- A global brand that once brought familiarity can now transmit controversy

- Country and corporate brands that once soared together can now stumble together

- A corporate structure that once merged global clout with local tastes now means a local owner or union can tank the global brand

And it no longer matters if you’re just selling chicken, coke, jeans, or a Barbie movie. To the contrary, it’s precisely these sorts of consumer-facing, ubiquitous, and highly competitive goods that are now the most vulnerable.

And when your bottom line is your north star, there’s a temptation to double down on neutrality, but this world of ours always finds a way to force choices.

Take Coke, which first entered Israel after facing a boycott back home for not entering Israel, only to then cop a 22-year boycott by the entire Arab League. Or look at the US apparel brands that’ve avoided boycotts at home by declaring they don’t use Xinjiang cotton, only to then face boycotts in China.

To boot, the results aren’t always predictable. When Coke cut links to its German team around WWII, the Germans ended up inventing Fanta. Meanwhile in today’s Malaysia example, it turns out one of the largest investors in the local KFC operator is also Malaysia’s largest pension fund.

So these days, it doesn’t really matter if you’re a Starbucks barista, a KFC janitor, a Domino’s franchisee, a pensioner, or a jet-setting CEO, anywhere in the world. To paraphrase Pericles: you may not be taking an interest in geopolitics, but geopolitics is taking an interest in you.