We’ve long been debating when to brief you on the shenanigans under the Baltic Sea, but another single undersea cable getting severed is never quite enough to beat a dictator’s downfall, a new US president, or a Wall St meltdown. And that’s precisely the point of hybrid warfare: it’s about inflicting pain that’s never quite enough.

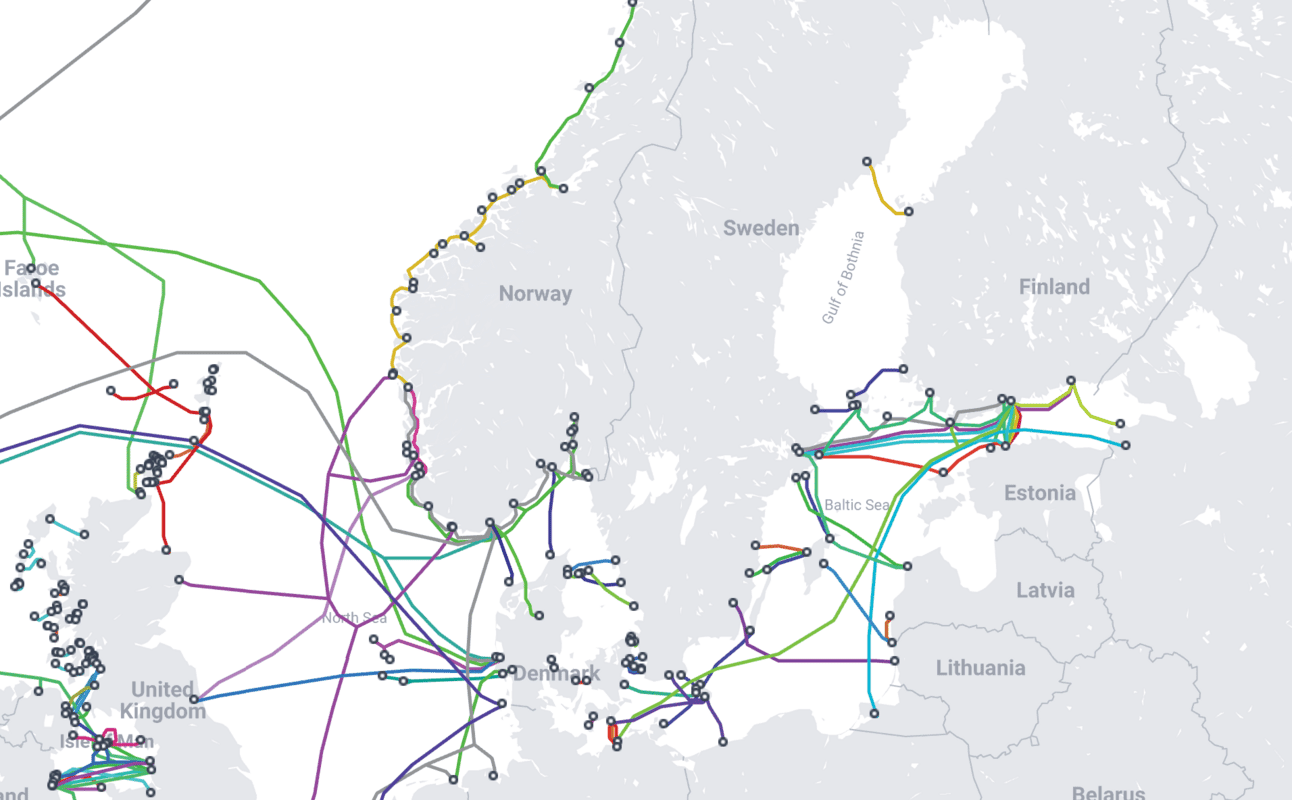

Any damage to critical infrastructure is bad, but when it’s the cables transporting 90% of our world’s entire telecommunications (official, private, military, etc), it’s serious.

Taken alone, individual cable incidents can often be chalked up to idiocy, inclement weather, or an earthquake. It happens. But when it happens repeatedly, in strategic locations, and due to rival-linked ships, a more sinister picture starts to emerge:

Stay on top of your world from inside your inbox.

Subscribe for free today and receive way much more insights.

Trusted by 129,000+ subscribers

No spam. No noise. Unsubscribe any time.

- In 2023, a China-based and Russia-originating ship dragged its anchor for hundreds of miles, rupturing a gas pipeline and two fibre-optic cables between Finland and Estonia. China later confirmed the ship was responsible, but blamed a weather-related accident.

- In November, two more undersea comms cables (connecting Sweden to Lithuania and Germany to Finland) were damaged within hours. After a diplomatic stand-off, Swedish police finally boarded the China-based and Russia-originating ship last month — the investigation continues.

- On 25 December, a power cable linking Estonia to Finland was damaged, and three more Finnish undersea cables were reported damaged the very next day. Finnish authorities are investigating an oil tanker linked to Russia’s shadow fleet.

- And just this past weekend, an undersea data cable linking Sweden to Latvia was damaged, prompting Swedish authorities to seize a Bulgarian-owned and Russia-departing ship on suspicions of sabotage, something its parent company denies.

In total, there’ve been 11 Baltic Sea cables damaged since October 2023.

So who’s to blame?

That’s a semi-tricky one, in part because this stuff does often happen due to ineptitude rather than ignobility — in fact, it happens on average 100 times a year, mostly due to fishing trawlers or ships dragging their anchors across the seabed.

But that’s exactly what makes undersea cable-cutting the perfect form of sabotage:

- It’s never big enough to trigger an immediate escalation, and

- It’s always got an element of plausible deniability.

These two factors combined make it hard for governments to calibrate a response. But as these incidents start to a) accumulate, b) harm NATO members, c) harm NATO’s newest members (Finland and Sweden are the common thread), and d) all trace back to Russia (and to a lesser extent China), that deniability starts to fade. The timing also matches Baltic state efforts to disconnect from Russia’s electricity grid in February.

Still, some believe the root cause is Russia’s use of a shadow fleet to evade sanctions — they’re crumbling ships with inexperienced crews, making accidents more likely.

Though you’ve gotta weigh that theory against the fact that some of these captains spent hours dragging their anchor a hundred miles while losing speed and disappearing off automatic tracking. That’s an odd combination to do by accident.

Russia’s motives would be clear: it’s part of a broader hybrid war against Ukraine’s supporters to impose costs, intimidate voters, sow chaos, undermine government credibility, chew up government bandwidth, and punish Sweden and Finland for joining NATO. It’s not just sabotage, but also assassinations, arson, cyber attacks, and beyond.

You could argue China’s motives are similar, given its ‘no limits’ partnership with Russia, plus the value of having Western governments distracted in Europe rather than focusing on Taiwan, Hong Kong, or the South China Sea. But Beijing has been semi-cooperative, and there are suggestions Russian intelligence might’ve just used local port visits to induce captains (including from China) to deliberately drop their anchors over cables.

So what have governments been doing about it?

We mentioned above the fact that limited scale and plausible deniability can make it tricky for governments to respond, but there’s another, more obvious factor, too: this underwater infrastructure is vast and, yes, underwater. That makes it tough to secure.

Still, European and NATO countries have been beefing up their maritime security and launched the Baltic Sentry mission earlier this month, including the deployment of frigates, maritime patrol aircraft, and a small fleet of naval drones.

The hope is that a more assertive security presence might deter repeats.

INTRIGUE’S TAKE

You can add undersea cables to the list of things looking more like a remnant from an earlier, globalised, US-led age — designed to drive globalisation, but now part of a reverse-Uno to inflict harm in a deglobalising world.

And we might soon add the West’s plodding response to that same bygone list — methodical investigations, occasional stern tweets, and now some extra patrols. This weekend’s latest incident suggests it all still might not be enough, though the West has its own options to inflict proportional pain in response.

Meanwhile, Putin’s implicit message here is that the pain stops when the West’s support for Ukraine’s self-defence stops. But this kind of hybrid warfare is really an expression of Putin’s weakness rather than strength — he’s still not managed to eject Ukraine’s counter-attacking troops from his own territory after six months, as his oil assets go up in flames, and his casualty numbers push towards a million.

Also worth noting:

- The UK last week accused Russia of sending a spy ship into British waters to map out underwater infrastructure.