We’re not a finance newsletter (we don’t own enough Patagucci vests to qualify), but we do enjoy scrolling through stock tickers.

That’s how we noticed some recent movements around Eutelsat, a Franco-British Low Earth orbit (LEO) satellite operator that’s in talks with the EU to ramp up its presence in Ukraine.

Over the past four days, the company’s stock prices have skyrocketed an eye-watering 650%. This is shortly after Moody’s had downgraded the company’s stocks into ‘junk’ territory as recently as January — so we were thoroughly intrigued.

Stay on top of your world from inside your inbox.

Subscribe for free today and receive way much more insights.

Trusted by 129,000+ subscribers

No spam. No noise. Unsubscribe any time.

Wait, why is this happening?

Primarily, it’s because Eutelsat is in the right place at the right time. Europe is increasingly looking to boost support for local strategic and defence companies (including LEO satellite companies) as it shoulders more of its own security burden.

Suggestions that Eutelsat could even potentially replace Elon Musk’s Starlink network in Ukraine then piqued the interest of retail investors, who bought the stock en masse, leading to a week of stellar growth for the company.

But while we’re not specifically interested in Eutelsat (it’s far from being an industry leader or innovator) we are very interested in the larger trend at play here: governments investing in LEO satellite constellations as a security need rather than a connectivity want.

But first, let’s spin back a minute.

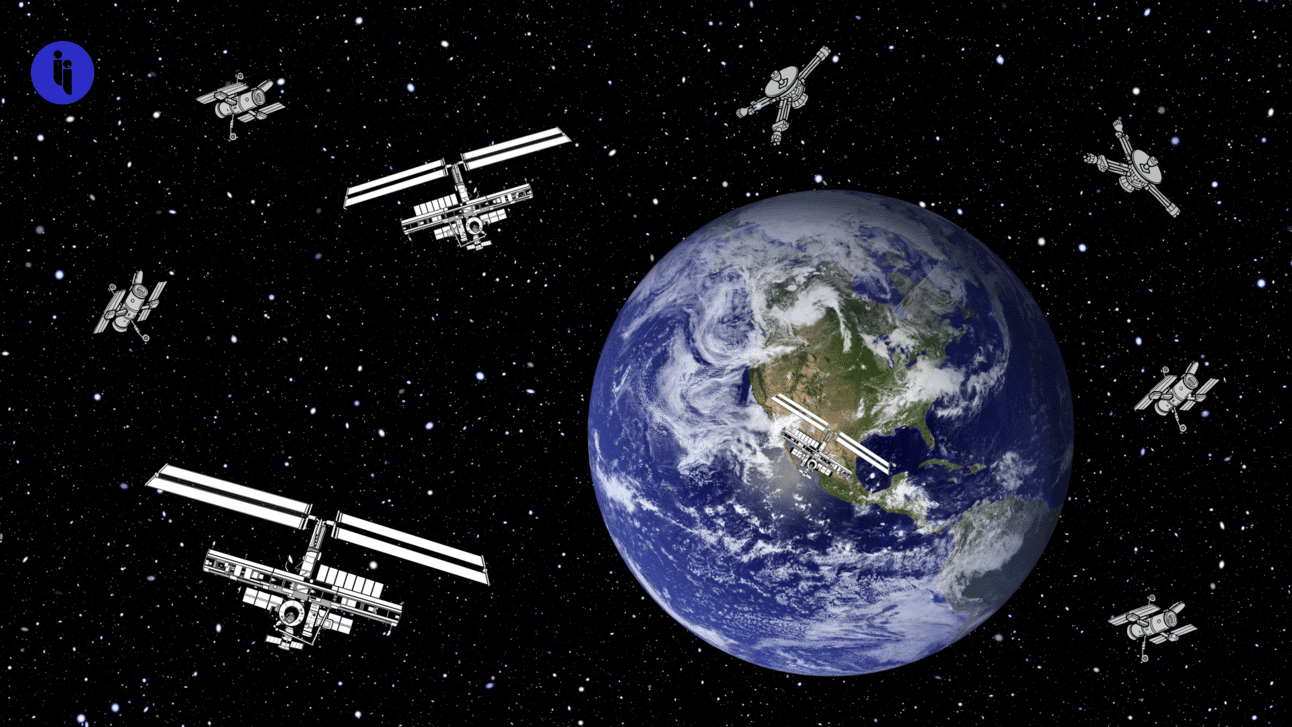

LEO satellite constellations are dense networks of small satellites offering high-speed internet to anyone with a terminal. Their lower orbit (anywhere within an altitude of 2,000 km/ 1240 mi) means faster internet speeds and better communication, although a large number of satellites are needed to achieve widespread coverage.

And they offer a key security advantage. Your normie internet mainly relies on global cable connections, whereas a satellite connection bypasses terrestrial infrastructure (like undersea cables), which is liable to accidental damage and sabotage. Plus, LEO satellite internet services are more easily deployable in remote areas.

Of course, LEO satellites aren’t without their own security challenges. For one, they can get hacked (in 2022, a cyber-security researcher hacked into one of Starlink’s dishes using gear worth $25). And secondly, they operate in an overcrowded and therefore sometimes accident-prone orbit space.

Regardless, it’s easy to see why some governments are increasingly interested in scalable and easily-deployable connectivity that offer alternatives to traditional networks during crises, both man-made and natural (e.g. last year’s Tonga earthquake).

But don’t take it from us:

Starlink satellites have been crucial in Ukraine, both for the military (which uses it to livestream drone footage and direct strikes) and civilians (who depend on the service for their daily lives). In fact, Kyiv has grown so reliant on Starlink that it now fears the Trump administration could limit access to the satellites as leverage in future negotiations.

And Kyiv’s not alone: Russia has also smuggled thousands of Starlink terminals onto the battlefield to boost its communications.

Taiwan, which recently detained a Chinese ship over suspicions of sabotaging an undersea telecoms cable, has pledged to spend over $1B to develop its own home-grown satellite internet network by 2026.

Several Chinese companies are also racing to launch their own mega-constellations of satellites, which China believes will benefit Beijing’s security and geopolitical influence.

And, as we orbit back to the start of this story, the EU is now in talks with its own LEO satellite dealer in an effort to secure future connectivity for itself.

INTRIGUE’S TAKE

The words ‘strategic assets’ get thrown around a lot these days. We increasingly see them in the form of countries ensuring they get unfettered access to the critical minerals and raw materials that are key to their supply chains, or militaries positioning themselves to protect important shipping routes and port infrastructure.

LEO satellite connectivity is now up there (sorry…) for governments as a strategic asset. It allows countries to have freedom of connectivity, which is increasingly vital for countries’ economic and military activities. Having access to LEO satellites from trusted providers is one of many challenges countries are quickly confronting in the space frontier.

Ultimately, there are still huge bottlenecks for entities looking to establish their own LEO satellite networks (including how to get them into orbit). It’s not cheap, so they’ll either need a space program — or have friends who are willing to let them use theirs.

Also worth noting:

- Starlink is by far the industry leader with over 7,000 operational satellites and over five million subscribers.

- Eutelsat and Starlink are amongst the companies competing for a secure satellite deal with the Italian government.