The US has agreed to withdraw its troops from Niger as the West African country joins several neighbours in pivoting towards Russia.

How’d we get here? A military coup last July ousted Niger’s democratically-elected president and long-time Western partner, Mohamed Bazoum.

The putschists, led by the head of the president’s own presidential guard, argued that Bazoum and his international partners hadn’t done enough to help quash the country’s Islamist insurgency.

Stay on top of your world from inside your inbox.

Subscribe for free today and receive way much more insights.

Trusted by 134,000+ subscribers

No spam. No noise. Unsubscribe any time.

And the celebrations on the streets suggested the coup had some popular support, particularly as heavy Western criticism reinforced local claims that former colonial powers like France were interfering in Niger’s own affairs.

Then days later, the new ruling junta ordered French troops to leave, before the US hit pause on most of its own local military operations (both Western powers were mostly focused on local armed groups linked to Al Qaeda and ISIS).

US officials then tried to salvage their own security pact until the junta announced last month – on TV – they were abolishing the deal. Niger didn’t directly ask the 1,100 US troops to leave, though noted their presence was now “illegal”.

That sent US diplomats scrambling in another last-ditch attempt to revise and renew their 2013 security agreement with Niger, but their efforts failed last week.

So, does a US withdrawal from Niger matter?

From a local perspective, folks say it’s about ditching arrangements that haven’t worked, and trying something else (see below). But for the US, this is all a little alarming because of what it does to US capabilities, and who might fill the gap.

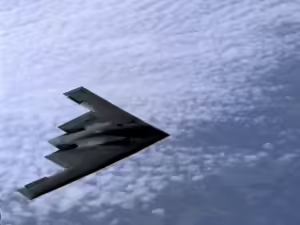

Local US capabilities rest mostly on Air Base 201, a $110M facility near Algadez that’s one of the largest US drone bases on the continent. It’s key for:

- Carrying out intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance missions

- Conducting emergency response (including to evacuate US citizens)

- Hitting the region’s Al-Qaeda and ISIS affiliates, which are now destabilising the region and causing half the world’s terrorism deaths, and

- Leveraging these capabilities to preserve US influence in West Africa.

In terms of who might fill the gap:

- Iran is reportedly in talks to tap Niger’s vast uranium reserves, potentially blurring international visibility of Iran’s nuclear program, and

- Russian troops landed in Niger just this month, bringing with them military trainers and, curiously, an advanced air defence system.

The arrival of an air defence system is particularly intriguing because local ISIS and Al-Qaeda affiliates don’t have any aircraft. So then what’s it for? Probably to help entrench the ruling junta in power, following last year’s threats from West Africa’s main sub-regional bloc (ECOWAS) to mount a military intervention.

And Niger isn’t alone in its Moscow tilt. Both Burkina Faso and Mali – fellow military rulers, neighbours, and now formal allies – are also working with Russia.

What’s in this for Russia? It’s about prying open access to strategic resources, while building a sympathetic bloc to counter Western pressure.

INTRIGUE’S TAKE

US security assistance in Niger clearly hasn’t met local expectations. In fact, most researchers say jihadism has actually gotten worse in the Sahel region.

Of course, the US might say the situation would be worse still, if not for the US investing a decade (and $1B) in local security. It could question how Russia’s Africa Group (the successor to its notorious Wagner mercenaries) will fare any better with a fraction of the resources. And it could highlight the likely cost, assuming the Russians will claim a slice of local mineral wealth.

But Niger’s ruling junta has now made its decision, apparently right after meeting with a visiting US delegation that was focused on democracy, Niger’s deal with Iran, and preserving the US security presence.

And clearly, the junta just wasn’t interested. So to us, this is an example of how Western leverage has eroded, not so much because Western power has faded, but because there are other players (with little interest in democracy or Iran) only too eager to step in. It’s happening elsewhere, too.

And it’s raising lots of uncomfortable questions for the US and its allies.

Also worth noting:

- Niger’s junta has held the ousted, democratically-elected president (Mohamed Bazoum) under house arrest with his family since last July.

- Russia’s new junta partners in West Africa (Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger) have since taken Russia-friendly positions at the UN, including on Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

- Earlier this week, at least six local soldiers were killed in a blast in Niger’s Tillabery region, near the border with Mali.

- The US is now negotiating the timing of its withdrawal from Niger, likely to take place over the coming months.