Diplomats don’t usually want to make headlines – in fact, it’s often a career-limiting move if you do! But diplomats from Argentina and Brazil are now in the headlines because, for the first time in history, they’ve just voted to go on strike.

Their joint timing is coincidental, though (ahem) it does come a week after we published the first-ever diplomat industry salary report (💅). So we’ve spoken to some of our friends in both services and, without getting too much into the weeds, the basic situation is this:

- Brazilians say there’s “widespread dissatisfaction among diplomats“, particularly around pay (eroded by inflation) and career progression (glacial). It’s just a vote at this stage – the actual strike details are still being hashed out and could be averted if negotiations succeed. In the meantime, they’ve legit just dropped an epic diss track 🤘 which they’re now blasting outside their foreign ministry (known as ‘Itamaraty‘).

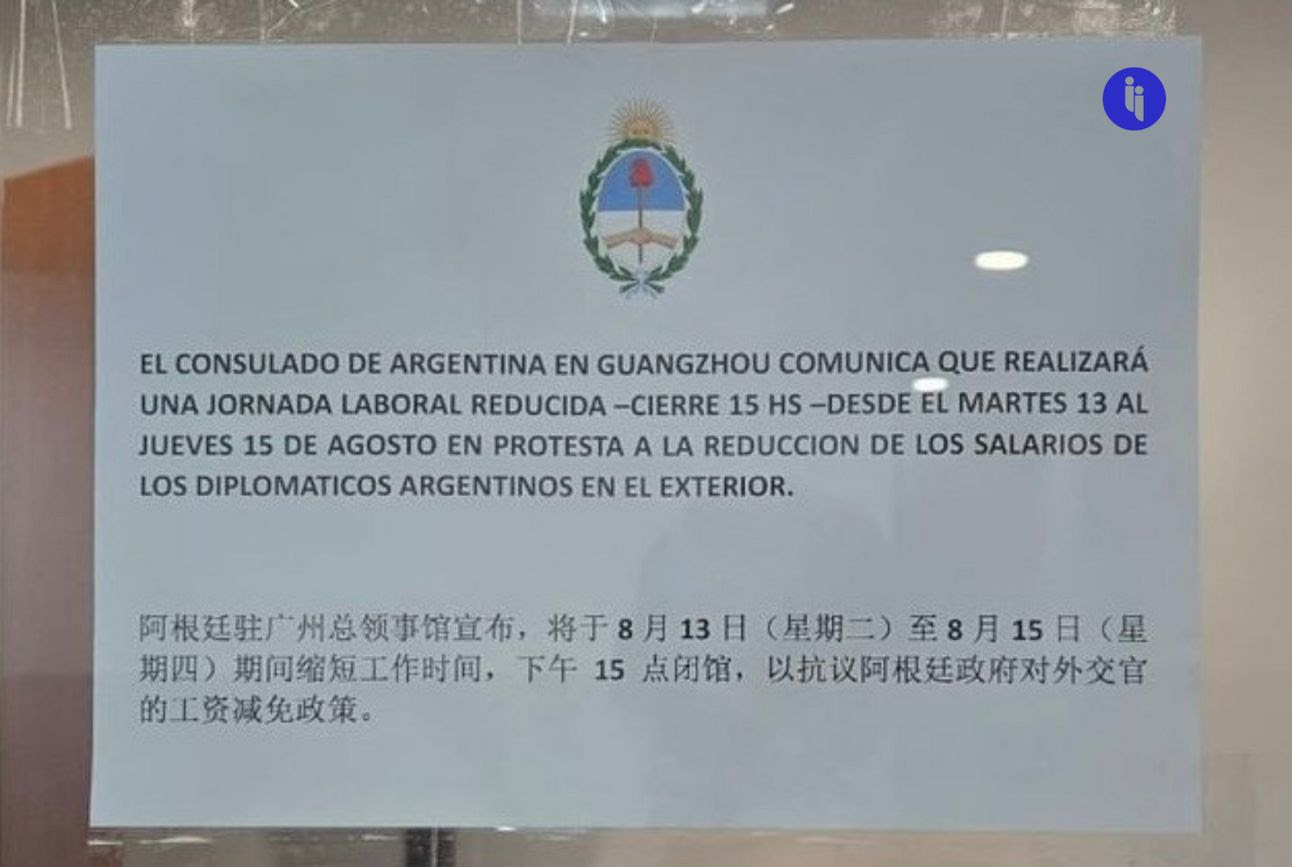

- Argentine diplomats aren’t well paid: a $35k mid-career salary doesn’t get you far if you’re serving in (say) New York – they pay their own rent, schooling, medical, etc. There’s an extra allowance, but their government is now taxing it, meaning an instant 20-30% pay cut. So Argentine diplomats are legit now figuring out which kid to pull out of school, or when they’ll be evicted, and they’re working reduced hours in protest.

So the details are a little different, and the national contexts are, too:

Stay on top of your world from inside your inbox.

Subscribe for free today and receive way much more insights.

Trusted by 134,000+ subscribers

No spam. No noise. Unsubscribe any time.

- For Brazil, this all comes at a time when its government is positioning itself at the centre of just about every conversation: whether that’s hosting this year’s G20, or next year’s COP and BRICS summits. So its diplomats are arguing you can’t push for that kind of heft on the world stage but then stiff the very people you’re tasking with getting it done.

- For Argentina, this all comes after President Milei swept to power on promises to cut spending, curb inflation, and halt the economic crises. His diplomats are steering clear of the politics, but it’s worth noting their pay cut comes despite Milei arguably making Argentina more active abroad, whether seeking: investment, the release of the 15 Argentinians held by Hamas, or the finalisation of the big EU-Mercosur trade deal.

Now, we’ll leave folks to make up their own minds on all the specific issues above, but they do raise some interesting questions below. First, the risks of striking:

- Will anyone notice? Unlike (say) striking nurses or train drivers, diplomats won’t bring a city to its knees. In fact, most citizens won’t even notice unless it hits their newsfeed. Which then raises the question…

- Will anyone care? Diplomats don’t naturally garner a lot of sympathy given their reputation as cocktail-swilling jet-setters. Yes, we’ve swilled the occasional cocktail (in the national interest) and set the occasional jet (in the national interest), but the career is much more complicated in our experience. Still, to the extent these strikes get attention, there’s the risk it won’t be kind – Brazilian media has been sympathetic so far. It might be a tougher sell in Argentina given the broad hardship there.

- Should diplomats strike? Each country has its own philosophy here, but many foreign ministries have no right to strike because as a national security agency, industrial action could theoretically harm the national interest. Critics of past strikes have also highlighted the risk of (say) visa delays causing a drop in visits by tourists, students, and investors.

- And has it ever worked? French diplomats went on strike without success in 2022, when Macron merged their centuries-old senior corps with a broader stream of civil servants. The Canadians had more luck a decade ago with their strike to close a wage gap. And Israeli diplomats went on strike last year against Netanyahu’s judicial reforms. For now, the Argentinians are hopeful the courts will side with them, while the Brazilians are hopeful they’ll reach a deal.

Second, the risks in not listening to them:

- Diplomats have access to classified material, and the ones in financial strife (and/or toxic workplaces) are more vulnerable to espionage

- The risk of WWIII is now openly debated by world leaders, and diplomats must inevitably be a part of figuring out how we avoid it, and

- A foreign service’s influence takes decades or more to build, but can be lost in a flash. That’s partly why the protesting French diplomats used lines like, “There’s no long-term diplomacy with short-term diplomats”

To close? Most foreign ministries are pretty cautious by nature, so for two to go on strike in a week – by an 80%+ majority vote in Argentina and 95% in Brazil – really suggests all’s not well. And that’s potentially a problem for everyone.

INTRIGUE’S TAKE

We loved our time in the foreign service. It’s an honour to serve, and we were often amazed by the work ethic, skills, and compassion we saw there. So we didn’t leave because we were disgruntled. In fact, you could call us ‘gruntled’.

But beyond the specifics of Argentina or Brazil, our sense is that this is all downstream of a few bigger issues that’ve been brewing for a while.

First, globalisation has meant foreign services no longer have a monopoly over presence, access, insight, or influence. That’s made their role (and value) harder to identify. So diplomats need to better articulate that to citizens back home.

But second, after the Cold War, many capitals lost their clarity of purpose and allowed their foreign services to atrophy, pushing them to irrelevance at home and impotence abroad. But now that the world’s gotten scarier again, it’s the national security agencies rather than diplomatic services that’ve grown, often proffering sharper solutions no matter how blurry the problems.

And third, against that backdrop, many ministries have become shackled by quirky subcultures that provide fodder for our resident meme lord (Jeremy), but which need to go: risk aversion, blame aspersion, waitocracy, over-servicing (“the soy milk not to your liking, minister?”), assumed incompetence (“my draft tweet is ready for your approval, ambassador”), learned helplessness (admiring rather than solving the problem), and so on.

The end result can resemble a sheltered workshop for the gifted and talented.

But all that aside, the last few years have been a reminder that there’s nothing impervious nor inevitable about our modern world’s bubble of relative security and prosperity. And so while there are valid criticisms of diplomats today, our world is not only going to need them more – it’s also going to need them at their best.

Also worth noting:

- Argentine diplomats already pay tax on their salaries. This new tax is on their allowances which enable them to survive abroad.