Thought you’d get a break from Western political turmoil? Think again!

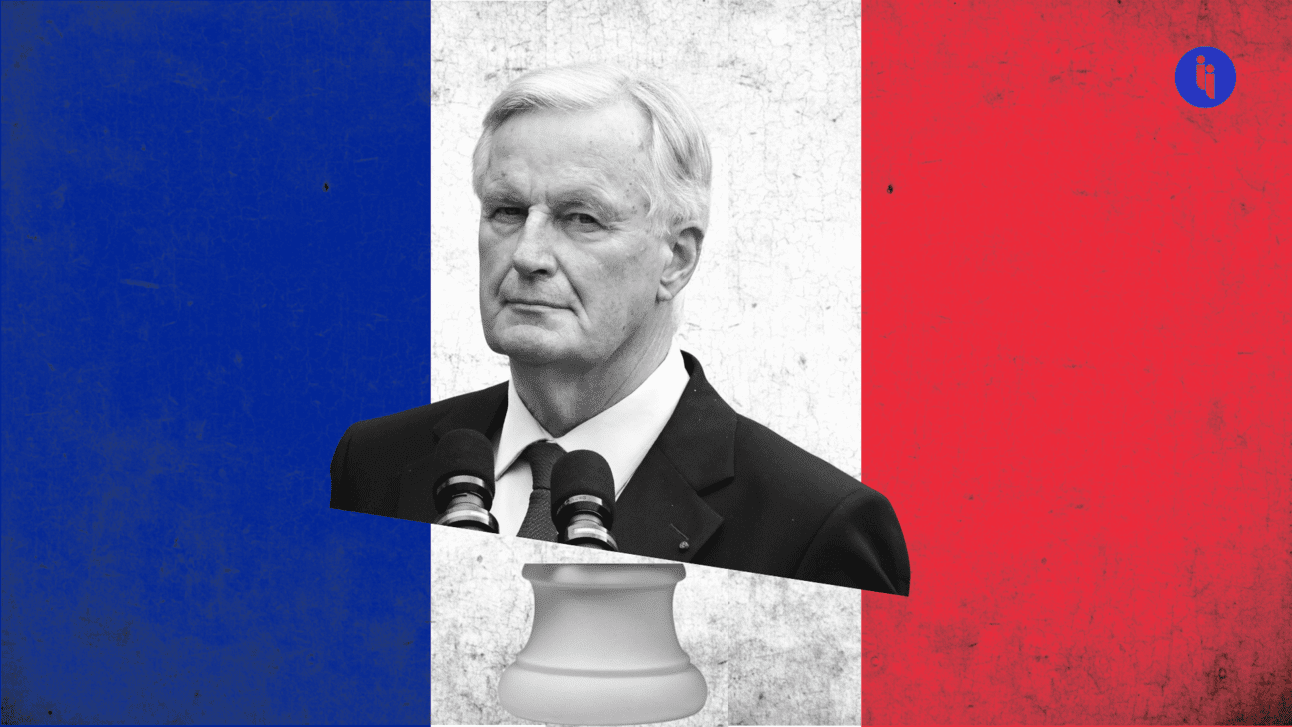

As we foreshadowed earlier this week, 331 of France’s 577 legislators cast ballots overnight (Wednesday) to oust the government of President Macron’s hand-picked prime minister, Michel Barnier.

The last time something like this happened in France? All the way back in 1962, when a government collapsed amid the fallout from the Algerian War of Independence.

Stay on top of your world from inside your inbox.

Subscribe for free today and receive way much more insights.

Trusted by 134,000+ subscribers

No spam. No noise. Unsubscribe any time.

But France’s latest political woes didn’t start this week.

Quick recap: France’s populist-right National Rally party (think Marine Le Pen) delivered a real beating to President Macron’s centrists at the EU’s parliamentary elections in June, so Macron then shocked everyone by calling his own snap parliamentary elections — he was basically betting voters wouldn’t pull that stunt again closer to home.

And was he right? Yes and no. Voters didn’t put the National Rally in power, but they didn’t put his own centrists back in power either. In fact, they put nobody in power, delivering an almost three-way tie between the left (182), centre (168), and right (143).

So Macron (whose own term runs until 2027) then had to figure out who could cobble the numbers together to form a new government. He went with centre-right former Brexit negotiator Michel Barnier, achieving the difficult balance of equally irking everyone just enough to keep the show on the road. But the left (who won the most seats and so wanted the top job) were particularly peeved, and rejected Barnier from the outset.

The result? Barnier’s only hope was the continued support of the right, and that’s what changed this week: Le Pen finally pulled her support, and Barnier’s government collapsed 90 days after he formed it. For those playing at home, that’s a crisp 8.1 Scaramuccis, and the shortest-lived government in France’s modern history.

Why did Le Pen pull her support?

Barnier is an old-school fiscal hawk and Le Pen is an old-school populist: so while Barnier was desperate to raise taxes and cut spending to get France’s yawning deficits back on a more sustainable track, Le Pen demanded that Barnier (for example) drop a proposed tax hike on electricity, and continue reimbursements for certain types of drugs.

Barnier kept playing ball, making $10.5B or so in concessions, until he drew the line at Le Pen’s last costly demand: keeping pensions in line with inflation. So she withdrew her party’s support, describing Barnier’s budget as “dangerous, unfair, and punitive”.

So, what’s next?

Macron now has to find a new prime minister who might cobble together the numbers to survive, but that’s not easy when you remember Barnier’s government was not only France’s shortest-ever, but also only emerged after France’s longest-ever negotiations.

So you might think okay, Macron should just call fresh parliamentary elections again to let the people decide, right? But France’s constitution only lets the president pull that stunt once a year, so he’s gotta wait until next summer.

Alternatively, fresh elections could happen if Macron resigns, something he’s already ruled out – but there’s a growing list of lawmakers (including Le Pen) now calling on him to go.

Meanwhile, Macron himself has just returned from a state visit to Saudi Arabia and will deliver a national address tonight (Thursday), though he doesn’t have many options:

- a) Find another centrist, but they’ll just bump up against Le Pen again

- b) Hand the reins to his rivals on the left or right, who see the world very differently, or

- c) Resign and trigger elections, which Le Pen could then win anyway.

Word is Macron wants to go with option a) again, with a new PM in place before the Notre Dame Cathedral’s reopening ceremony on Saturday.

INTRIGUE’S TAKE

So what does all this palace intrigue mean for the rest of us?

First, there’s a risk this political crisis could metastasise into a broader financial one. France’s projected deficit of 6.1% of GDP has already spooked investors, and startled the EU (which now limits deficits to 3% of GDP).

But second, a national crisis in France can quickly evolve into a regional one — with each day that Europe’s key powers (France and Germany) are both mired in domestic turmoil, the chances of them driving solutions to Europe’s challenges get slimmer.

Also worth noting:

- Barnier is scheduled to visit Elysée Palace this morning (Thursday) at 10am local time to formally present his government’s resignation. While he could stay on in a caretaker role, it’ll be up to his successor to solve the budget crisis.

- If France’s lawmakers can’t approve a new budget for 2025, the old budget basically gets repeated as an emergency measure — this averts a US-style government shutdown, but allows France’s financial woes to worsen.